You know Ginko trees, those numbers with the stanky yellowish berries that I, and perhaps you, called “stinky trees” as a wee lad? Well, I ate some of that stank.

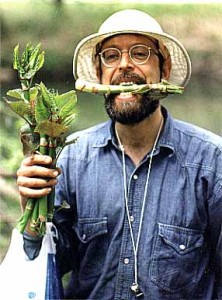

This came about because Shannon is awesome and for an anniversary present took me deep into Queens to spend an afternoon with Wildman Steve Brill. A name like Wildman  primarily conjures in me images of either a crazed and burly mountain man type or a happily-hard-livin drummer in a band opening for Dokken in 1987, but Steve Brill fits neither of these molds. In fact, this is the picture he has of himself on his website, which more perfectly sums him up than anything I could write this morning.

primarily conjures in me images of either a crazed and burly mountain man type or a happily-hard-livin drummer in a band opening for Dokken in 1987, but Steve Brill fits neither of these molds. In fact, this is the picture he has of himself on his website, which more perfectly sums him up than anything I could write this morning.

Our afternoon with Steve, billed by Shannon as “New York’s top wild food foraging expert,” was spent walking Forest Park learning about and filling up a bag with wild roots, berries, and greens (or weeds, if you want to be classist) that we could incorporate with dinner. It was nothing less than unflaggingly awesome.

Awesome Fact: The Ginko is a survivor from the Jurassic. Known only by its fossilized leaves, it was assumed extinct until a few specimens, somehow protected from the glaciers, were discovered tucked away in valleys in China. They now have no natural predators. Everything that ate them has gone extinct.

The Ginko tree was the first and, for me, most exciting discovery. That anything as universally disdained as the flatulent berry of that tree could be eaten and enjoyed by a sensible human being makes me very, very happy. You eat the seed of the Ginko berry, described by Steve as tasting like a combination of a pea and Limburger cheese. The process is simple: you peel away the fruit, wash the seed, and dry roast it with salt and pepper for about half an hour at 350 degrees. When slightly cooled, crack the thin shells and eat the meat inside.

The result is one of the most unique foods I’ve ever tried, a seed-like, pale green kernel with the texture of a slightly gummy custard, a spicy and piquant nuttiness, and an undertone of the aforementioned stank, otherwise classified by Steve as Limburger’y. Though these are safe, eat only a few at first because some people’s stomachs flinch.

Over our four-plus hours with Steve we were taught how to identify and forage wild burdock root (which, according to Steve, cleans the blood and helps acne) and episote (good for seasoning Mexican foods and, as a tea, a solid hangover helper) as well as wild onions and Garlic Mustard and Sweet Cecily, licorice-flavored green that looks pretty much exactly like parsley. We found sarsaparilla that can be turned into tea or soda. We gathered Black Walnuts and were told that their taste is so strong you can substitute them for only a third of the walnuts used in a given recipe and the whole thing will taste of the wild variety. We collected Black Birch twigs that taste of wintergreen, are the template for modern aspirin, and can be turned into a tasty tea that replicates aspirin’s effects. Approximately five cups steeped at 20 minutes equals one standard aspirin.

And we collected all kinds of wild greens that are as healthy as the day is long and can be prepared just like kale chips. Bitterdock leaves were the longest, so we used them for our first run at making wild green chips. We prepared them just like kale chips (brushed with olive oil and seasoned with salt and lemon pepper and chili powder) and they were delicious, flaky and spicy with a mild bitter afterbite.

The fact that all of this grub is right under our noses and generally ignored—and that until a few generations ago we collectively knew about this bounty for tens of thousands of years—is so exciting to me its almost embarrassing. This is buried treasure stuff. Also worth noting, and I found this surprising, is the fact that the urban environment is vastly superior to the suburbs for finding this stuff. Why? The deer out there in the cul de sacs are fierce competitors.